This month the American Chemical Society designated the research of Merck & Co., Inc., on the vitamin B complex as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in a ceremony in Rahway, New Jersey. The story of the discovery of the vitamin B complex begins in 1889, when a Dutch physician named Christiaan Eijkman, working in the […]

This month the American Chemical Society designated the research of Merck & Co., Inc., on the vitamin B complex as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in a ceremony in Rahway, New Jersey.

The story of the discovery of the vitamin B complex begins in 1889, when a Dutch physician named Christiaan Eijkman, working in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), was investigating beriberi, an endemic condition that caused weakness, weight loss, confusion, and sometimes death. The disease was common in areas where refined rice comprised a large portion of the diet, such as in southern and southeastern Asia.

Eijkman studied the effects of dietary variations on the occurrence of beriberi. He observed that chickens fed a diet of machine-polished white rice developed symptoms similar to beriberi, while those served unpolished brown rice did not.

In 1906, English biochemist Frederick Gowland Hopkins suggested a connection between nutrition and diseases like beriberi and scurvy. Hopkins had conducted feeding tests on animals, providing them diets of purified fats, proteins and carbohydrates, only to discover that the combination failed to sustain growth. Hopkins reasoned that there must be essential nutritional substances outside of these categories, which he called “accessory food factors.”

In 1911, Casimir Funk, a Polish biochemist working in London, further advanced this idea. He proposed that hitherto unknown organic substances, which he called “vitamines,” were required in tiny amounts in order to maintain health. This word combined the words “vital” and “amine,” a nitrogen-containing group in organic molecules. (Researchers later found that not all vitamins possess amine structures, but the term had already caught on, though without the final “e.”) In 1913, University of Wisconsin biochemist Elmer McCollum was able to distinguish two different species of vitamins, which he called “fat-soluble factor A” and “water-soluble factor B.”

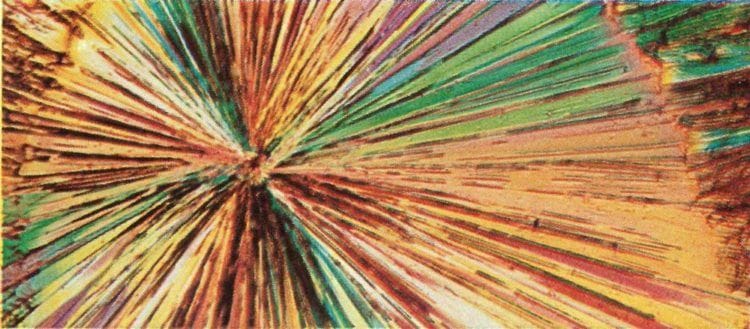

In 1926, Dutch chemists Barend Jansen and Willem Donath, also working in the Dutch East Indies, isolated crystals of the anti-beriberi factor from extracts of rice polishings. Eijkman tested the compound and found that it cured the disease in birds. The anti-beriberi factor was the first vitamin to be isolated, confirming the theories of Hopkins and Funk. It was later named vitamin B1 or thiamine (also spelled thiamin).

Chemists throughout the world raced to isolate, characterize and synthesize vitamins. Merck had already begun this task by the 1930s, but reports of progress by others in the field accelerated the company’s efforts. When Robert Williams of Bell Laboratories (who had previously investigated the anti-beriberi factor in the Philippines) approached Merck to help isolate and produce thiamine, the company’s research division enthusiastically embraced vitamin research.

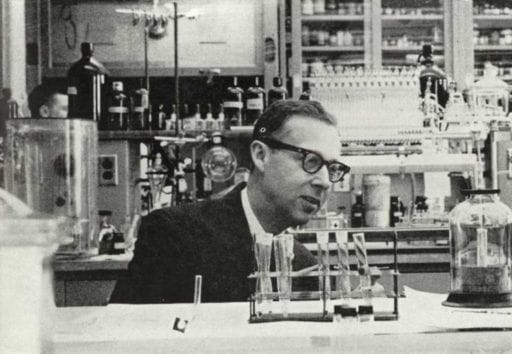

Randolph Major was chosen to head the new research and development laboratory Merck built as part of its efforts to grow basic research. Merck was quickly able to isolate thiamine and test it in humans. In 1936, Williams and a young organic chemist at Merck named Joseph Cline synthesized the vitamin, beating out competing teams from Germany and England.

Within a few years Merck was producing thiamine commercially by means of a challenging 15-step synthesis, a highly complex undertaking for a pharmaceutical company at the time. Vitamin-enriched foods, particularly bread flour, were popularized as a means to reinstate the vitamins that were lost in grain processing.

Merck ramped up its work on vitamins. Company leaders announced an initiative to research every vitamin—to isolate, determine the structures, synthesize and market them. New talent was brought in to advance these efforts, including chemists Karl Folkers in 1934 and Max Tishler in 1937.

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) had been discovered in 1922 by Richard Kuhn in Germany and Theodor Wagner-Jauregg in Austria. The compound was isolated in 1933 by Kuhn and Paul György in Germany. Kuhn also developed a synthetic route to riboflavin which was licensed to the German company I. G. Farben; meanwhile, in Switzerland, Hoffmann-LaRoche held patents for another method of synthesis from Paul Karrer. Because the two companies refused to license their methods to Merck for riboflavin production in the U.S., Tishler’s first major task was to develop an alternative method for industrial synthesis. This was achieved within two years.

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) was discovered in 1934 by György and colleagues, and the active compound was first isolated by Samuel Lepovsky of the University of California, Berkeley, in 1938. Folkers and his Merck colleague Stanton Harris determined the structure of pyridoxine in 1939, simultaneously with Kuhn in Germany. The synthesis of vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) followed, reported by Merck in 1940.

The final chapter of the B vitamins was among the most challenging. In the mid-1800s, physicians in England had identified the disease pernicious anemia, a disorder that results in too few red blood cells being produced in the body. The disease causes subjects to feel tired and breathless, and it can be lethal.

In 1926, a team of physicians from Harvard University discovered that eating half a pound of liver every day would prevent pernicious anemia in most patients. From this point, researchers worldwide sought to isolate the anemia-preventing substance from liver.

Prior to the search for this vitamin, animal screening was used to test the effects of various diets and nutrients. But for pernicious anemia there appeared to be no suitable animal analog of the disease. The only alternative then available was to conduct tests on human patients. Folkers worked with Randolph West of Columbia University to find patients willing to participate and feed them various liver extractions. The researchers worked slowly, forced to wait weeks in their search for patients with pernicious anemia due to the rarity of the disease.

A fortunate coincidence led to a critical advance: Folkers learned that microbiologist Mary Shorb had identified a bacterium that responded to liver extracts. Folkers recognized that the bacteria could be used as a stand-in for human subjects, and he brought Shorb to Merck

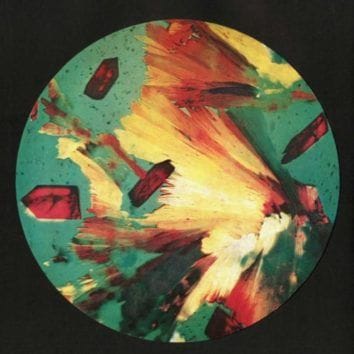

The researchers recognized that the liver extracts that produced the most promising effect in Shorb’s bacteria were pinkish in color—suggesting that the sought-after vitamin was a red compound. In 1947, Folkers and his team isolated vitamin B12 (cobalamin), producing tiny, bright red crystals of the vitamin. The following year, this new compound was tested on a patient who suffered from pernicious anemia, curing her.

Cobalamin was later found to be a key growth factor in animals. This realization led to the practice of enhancing animal diets with the vitamin, which led to greatly increased yields for livestock farmers.

Before the discovery and widespread availability of vitamins, diseases caused by malnutrition took an incalculable human toll. Research and development of these essential nutrients represented a transition for pharmaceutical companies like Merck. Their work vastly improved the health of humans and animals by overcoming the scourge of malnutrition.

Much of the research relating to the isolation and synthesis of B vitamins was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, including work on the increased isolation of B1; structure of B1; synthesis of B1; synthesis of B2 and new synthesis of B2; structure of B6; synthesis of B6; synthesis of B5; and isolation of B12.

Learn more about ACS’ efforts to recognize important discoveries in the history of chemistry.