This year’s aggressive flu season reminds everyone that although the flu vaccine can reduce the number of people who contract the virus, it is still not 100% effective. A tweak to a small-molecule drug shows promise for future production of new antiviral therapies that could help patients, regardless of the strain with which they are […]

This year’s aggressive flu season reminds everyone that although the flu vaccine can reduce the number of people who contract the virus, it is still not 100% effective. A tweak to a small-molecule drug shows promise for future production of new antiviral therapies that could help patients, regardless of the strain with which they are infected.

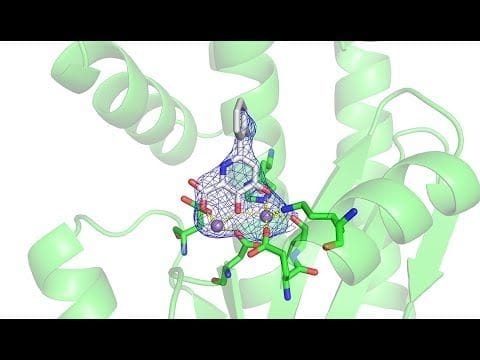

In order to develop an antiviral drug for influenza, scientists had to find an area within its structure that would prove vulnerable. The influenza virus is a lipid-enveloped, negative-sense, single-strand RNA virus, meaning the genetic information it uses for replication is contained in RNA strands held inside a protein shell that is coated by a fatty layer. Instead of relying on a host’s straightforward DNA replication process as some other viruses do, influenza depends on its own enzyme called RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. So, scientists have consistently focused research efforts on developing a drug that would affect this viral process.