A recent study presents a quick, effective method for sticking soft matter together without the need for glue.

Most of us likely have a story or two about how glue has come to the rescue in our daily lives. From arts and crafts to automobiles, there seems to be a glue available for almost every material, activity, or fix-it situation. There’s even skin-safe liquid adhesive you can apply to minor cuts and scrapes in lieu of traditional bandages. But what about when it comes to sticking softer, more delicate matter together, such as human organs and tissues?

A new study published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces presents a novel technique for adhering soft materials to each other, ditching the glue entirely in favor of an electrical current. The researchers, from the University of Maryland, United States, had previously used this “electroadhesion” method to successfully adhere a gel to an oppositely charged tissue. However, the team wanted to take their research even further to see if electroadhesion could work on any two soft materials with opposing charges and be used to build more complex 3D structures.

A Power Source That Sticks

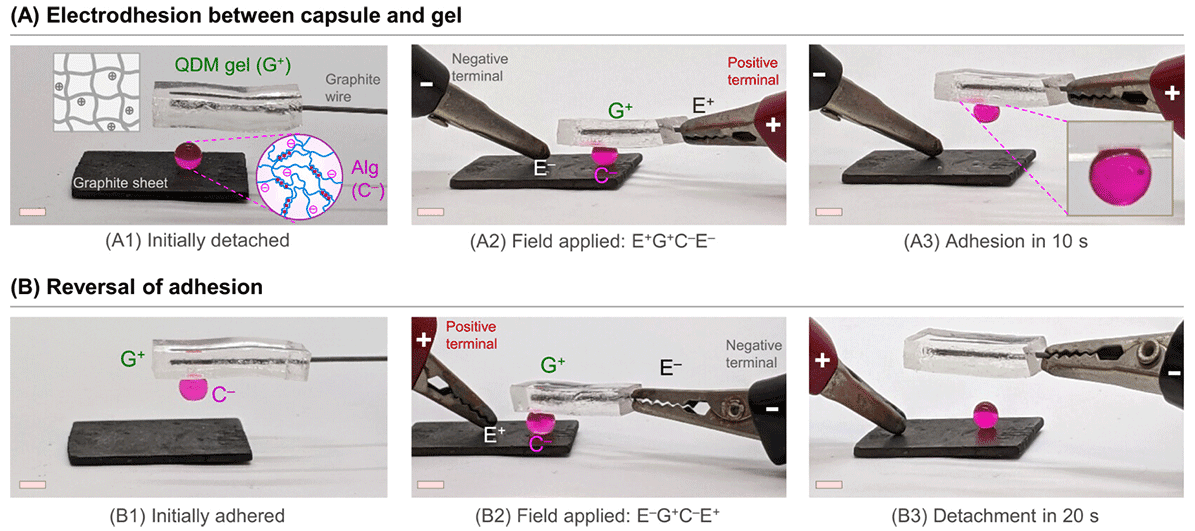

To do this, they prepared a positively charged gel strip and three types of biopolymer-based capsules, each holding a positive or negative charge. First, they paired the gel with a negatively charged alginate capsule and connected each to a graphite electrode. Upon applying a 10 V electric field, the gel and capsule adhered to each other within 10 seconds, remaining strongly intact after the current was turned off and able to withstand gravity when lifted with a magnet. Upon reversing the polarity of the electric field, the gel and capsule easily detached from each other within 20 seconds.

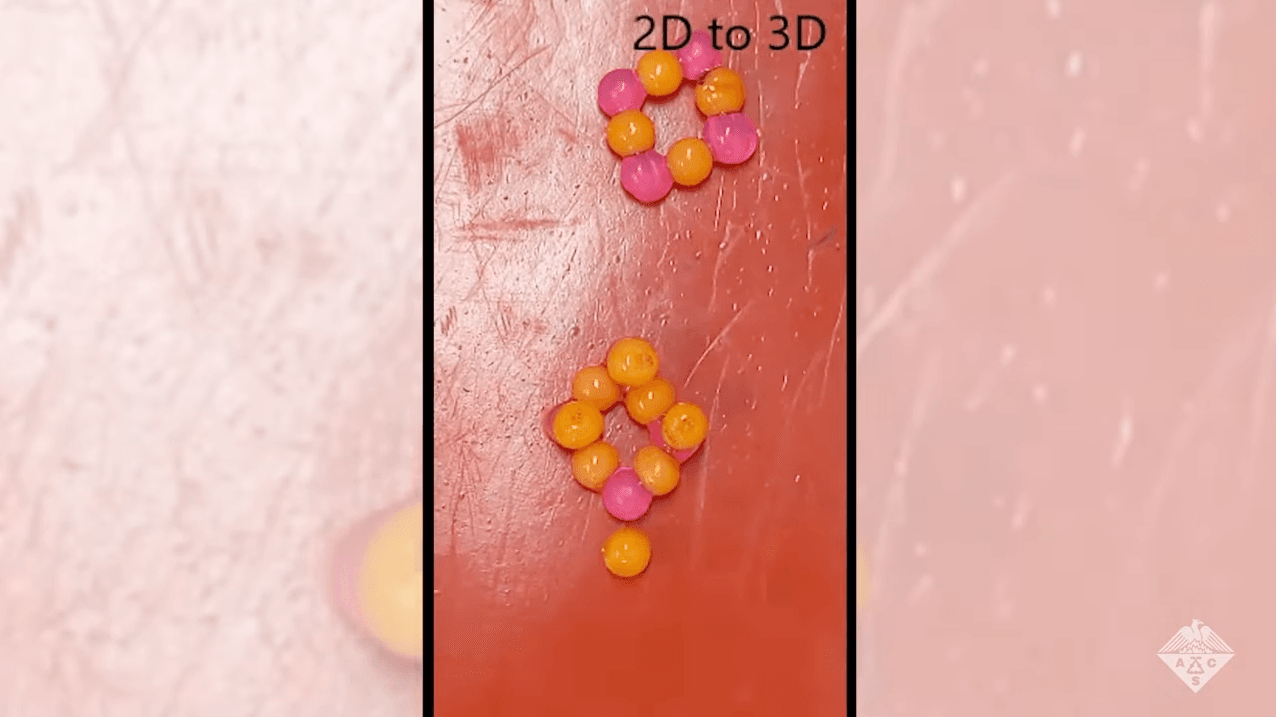

The researchers were then able to adhere positively and negatively charged capsules to each other and use them as “building blocks” to construct chains, 2D patterns, and 3D cubes. Lastly, the team demonstrated the ability to selectively pick up specific capsules from a graphite sheet using a 3D-printed, gel-covered “finger robot” with an opposing charge.

These findings demonstrate the promising potential of electroadhesion as a universal method that works effectively across a variety of soft structures, and the authors report that this technique may one day be used in applications such as tissue engineering and robotics.

Watch electroadhesion in action in this video created by the ACS Science Communications team: