The peer-review process can appear intimidating and complex. However, it is an essential element of scientific publishing, ensuring that a manuscript is relevant and suitable for publication and upholding scientific integrity. Peer review helps to maintain high standards for published research. This post will walk you through the peer-review process, show you how reviewers are […]

The peer-review process can appear intimidating and complex. However, it is an essential element of scientific publishing, ensuring that a manuscript is relevant and suitable for publication and upholding scientific integrity. Peer review helps to maintain high standards for published research. This post will walk you through the peer-review process, show you how reviewers are critical to the success of the process, and give you the tools to become a reviewer.

Peer review is the practice of subjecting scholarly work to the scrutiny of experts in the field (i.e., you, the reviewers) with the goal of validating and improving the content before publication. The peer-review process covers every aspect of your scientific contribution, including your approach to the problem, experimental design, execution of your studies, interpretation of your results, and your scholarly presentation and effectiveness of communication. If you’ve authored a scientific publication, you’ve benefitted from the peer-review process.

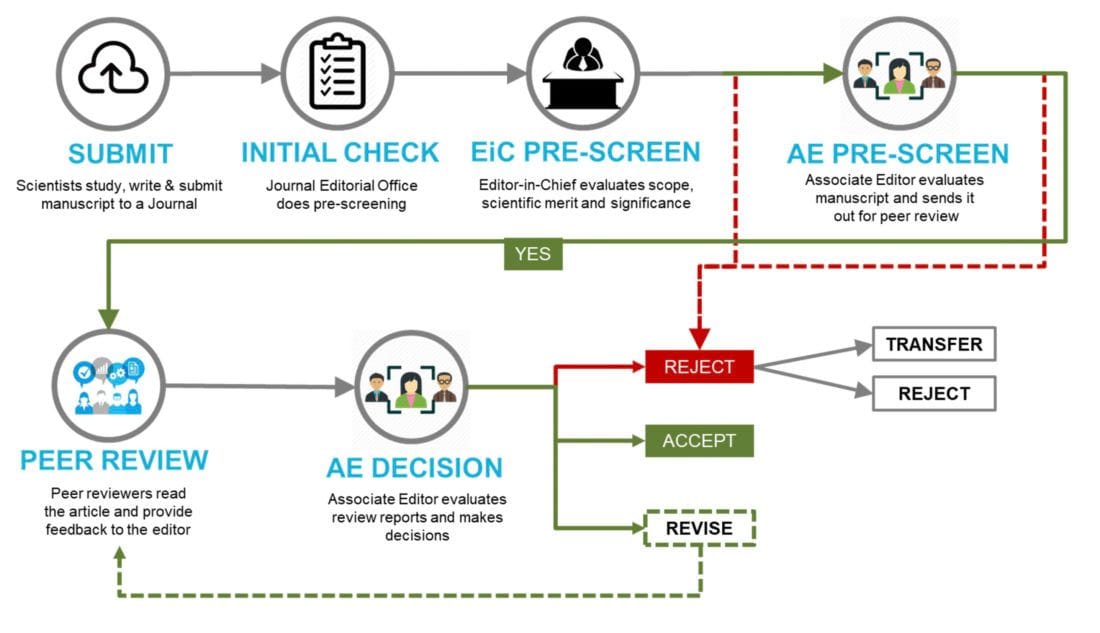

The peer-review process starts when you submit your manuscript to the journal through a system such as Paragon Plus, as shown in the flow diagram below. Once submitted, the process begins with a series of pre-screening steps by the editorial office, the Editor-in-Chief, and Associate Editors. Upon passing those evaluations, the manuscript is then sent to reviewers for feedback. Once the feedback has been received, the Associate Editor determines whether to reject the manuscript, accept without revision, or return it to the authors for revision (multiple times if necessary). If a revision is successful in addressing reviewer feedback, the manuscript will ultimately be accepted for publication by the journal.

Learn More About the Individual Step in the Peer Review Process:

Editorial Pre-Screening

After initial checks by the journal editorial office, the Editor-in-Chief (EiC) evaluates the manuscript to ensure that it fits the scope of the journal, has novelty and urgency, has technical validity, and is of high quality. This pre-screening process is critical to not overburden the reviewer pool and to ensuring timely decisions on manuscripts. Manuscripts not meeting the standards of the journal can be rejected at this point in the process. Meanwhile, those deemed acceptable are assigned to Associate Editors for further screening and action. It is worth noting that the Associate Editors can also determine whether a manuscript meets journal standards, rejecting the manuscript if necessary. Once the assigned Associate Editor determines the manuscript warrants further review, they move on to the next step in the process: selecting reviewers.

Selecting Reviewers

Reviewers are drawn from two different sources: an independent pool of experts maintained by the journal and preferred reviewers recommended by the authors of the manuscript. Regardless of the source of the reviewer, the Associate Editor selects reviewers based on their broad knowledge and understanding of the field; their technical expertise to evaluate the experiments, data, and interpretation; and their ability to offer constructive, fair, and unbiased opinions of the manuscript. As an author, when selecting your preferred reviewers, you should be sure to avoid friends, collaborators, or anyone who could have a conflict of interest.

Reviewers are given a specific (yet, flexible) due date to submit their feedback to the Associate Editor to maintain reasonable timelines for decision-making. Once a sufficient number of reviews have been received, the Associate Editor moves to the next step: making a decision.

Making a Decision

The Associate Editor has several decisions for which they can opt, but they generally fall into three main categories: accept, reject, and revise. To determine which path is most appropriate, the Associate Editor first reads and analyzes each reviewer report alongside the manuscript. Associate Editors will specifically look to see if the manuscript requires revisions or additional experiments to address reviewer feedback and concerns. Once the decision is made, it is communicated to the corresponding authors of the manuscript.

If the decision is to accept the manuscript, no further revision is required, and the manuscript proceeds as is to the publishing office. A decision to accept may come after the initial round of peer-review, or more frequently, following one or more rounds of revision.

If the reviewers provided generally positive feedback but indicated that the manuscript requires some level of revision or addition of new experiments and data, a decision for either major or minor revisions will be communicated. Typically, a decision for major revisions provides the authors more time to address the feedback and will often require additional reviewer feedback following revision to ensure the feedback has been adequately addressed. Several rounds of review and revision may be required to ensure the manuscript meets the journal standards and sufficiently addresses the reviewer’s comments before ultimate acceptance.

Finally, if the majority of the reviewer feedback indicates that the manuscript is not suitable for the journal and will not be improved sufficiently upon revision, a manuscript will typically be rejected. In select situations where a manuscript is rejected primarily based on journal scope and fit, a rejection may be accompanied by an offer to transfer the manuscript to a more suitable journal within the same publishing group. This can be a fantastic way to reduce review time at the new journal by leveraging feedback already provided during the first review with the original journal.

Successfully Dealing with Rejection

From the flow diagram of the peer-review process, you’ll see that there are several decision points where a manuscript may be rejected by either an Editor-in-Chief or Associate Editor. Receiving a rejection can be demoralizing, disappointing, and stressful. Many authors, myself included, have had (multiple) manuscripts communicating years of effort rejected by scientific journals throughout their careers. While your initial reaction might be to feel angry or defensive, there is always the opportunity to successfully lead a rejection toward a positive outcome. Making lemons out of lemonade depends on understanding why your manuscript was rejected by the journal.

If an Editor-in-Chief or Associate editor determined during pre-screening that the manuscript did not meet the journal’s defined scope or standards and you disagree with the decision, you may contact the editorial office and request an explanation. It is possible to appeal the decision if you believe that the significance of your work has been overlooked, but doing so is uncommon and should be done judiciously.

If your manuscript has been rejected after peer-review, it is sometimes best to take a step back after reading the reviewers’ comments to refocus on the science. Approach the comments with a growth mindset and ask yourself how you could improve the content of your manuscript and the communication of that content to your intended audience. Update your manuscript and resubmit to either the same journal or a different one better suited for your work.

Responding to Reviewer Comments

When you receive reviewer comments on your manuscript, you’ll need to address them through the revision process promptly. Whether you add new experiments or update the text to better explain the existing content, you’ll need to provide a point-by-point rebuttal of all the reviewer comments with your revised manuscript.

When I read reviewer comments, I try to approach them with a mindset focused on the audience’s experience and understanding of the manuscript. Essentially, a reviewer’s feedback represents a gap between what my manuscript communicates at the moment and what I want the manuscript to communicate about my research. In revising a manuscript, I think about how I can best bring the audience closer to my intended message and experience. By helping the audience see your research the way you see it, you will more effectively communicate your achievements and improve the impact of your work.

How to Become a Reviewer

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve hopefully noticed that the reviewers are the engine of the peer-review process. Sustainability of the peer-review process depends on journals and editors cultivating a broad pool of independent experts. Three ways to become a reviewer are to establish your expertise in your field, seek out training and practice, and advocate for yourself. By authoring your own published research, attending conferences, networking, and building an online presence, you can enhance your standing and expertise in the scientific community.

The ACS Reviewer Lab is a free online training course that offers hands-on training for new reviewers. Upon completion of the training, it will be reflected in your ACS Publications profile in Paragon Plus that editors like myself can see when selecting reviewers for new manuscripts. Finally, you can advocate for yourself with your research advisors or colleagues in your network. They can list you as suitable alternative reviewers when they are unable to accept an invitation. Reach out to journals directly to indicate your interest in reviewing manuscripts, including your CV and publication record. Serving as a reviewer is one of the most rewarding professional activities available in our field, often bringing you tangential benefits as an author as well.

Anatomy of a Good Review

This table highlights the elements editors expect when receiving feedback from a reviewer on a manuscript.

In general, the information included in a review is visible to both the authors and the editors with one exception. There is space allocated to share comments only with the editor; some examples of what may be included in this section is information regarding potential conflicts of interest, scientific misconduct, or if you reviewed the manuscript for another journal.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the reliability and sustainability of the peer-review process depend on you, the reviewers, to provide feedback for authors to improve the quality and effectiveness of scientific publications. The scrutiny of our peers is central to upholding scientific integrity and maintaining high standards for published research. The core partnership between authors, editors, and reviewers builds enduring trust in the peer-review process, to the benefit of our field and society at large.